Anthony Burns

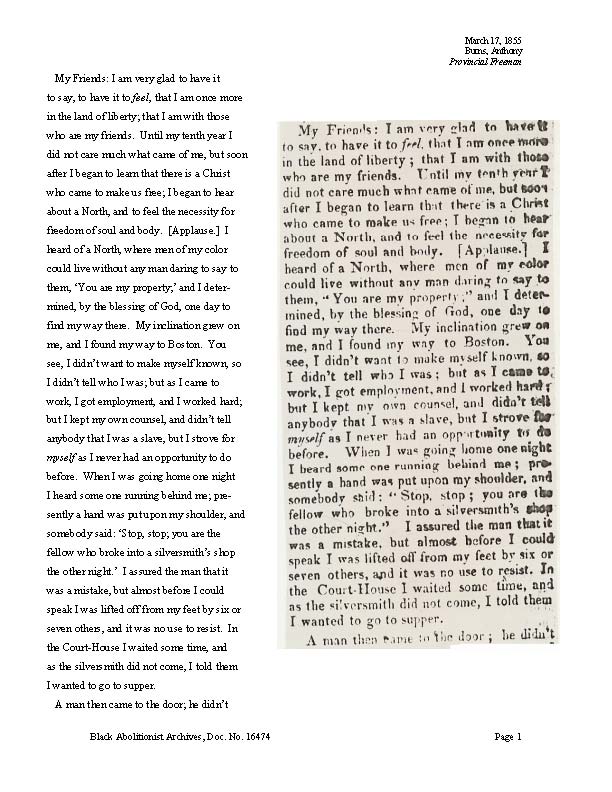

Those of you who have visited the Black Abolitionist Archive have likely noticed the photograph of a young man named Anthony Burns in the upper left-hand corner of the main page. There’s an interesting history to this young man’s experience that helped to bring to light the depth of the outrage of slavery, and to change the hearts and minds of the citizens of Boston. Through his own words we learn of his plight.

When Anthony Burns was 19 years old, he mustered enough courage to escape from slavery in Virginia and make his way to Boston. He found a job with a local merchant and kept to himself. He believed he’d found the freedom he so desperately sought in the solitary life he’d chosen for himself in Boston. Then he made a fateful mistake.

Historynet.com fills in the blanks of Burns’ story and describes how he sent a letter to his brother, also a slave held at the same plantation in Virginia, disclosing his whereabouts. The letter was intercepted by the plantation owner who traveled to Boston to retrieve his “property.”

Boston was a good place for Burns to be. The people of this city had long disagreed with the Fugitive Slave laws that now determined Burns’ fate. And at this point, there were opposition forces gathering together to take action in Burns’ defense, radical action association with an underground Vigilance Committee group. (The Burns’ arrest took place around 1854. In 1859, just five years later, John Brown would shock the country with his raid on Harper’s Ferry.)

The Boston Vigilance Committee (BVC) secured an excellent legal defense for Burns free of charge. But before any legal proceedings could take place, rioters, organized by the BVC stormed the courthouse in an effort to free Burns.

Historynet.com describes it this way:

The BVC organized a huge meeting for the evening of Friday, May 26, at Boston’s historic Faneuil Hall. Some 5,000 irate antislavery protesters attended. Wealthy merchant George Russell, a founding member of the BVC, opened the meeting and immediately set the tone: “The time will come when Slavery will pass away…. I hope to live in a land of liberty — in a land where no slave hunter shall dare pollute with his presence.”

The rioters were turned back; one man was killed; and the trial proceeded. Though his legal defense was impassioned and would prove historic, in the end, Burns was returned to the plantation with his former master. At their parting, the plantation owner jeered at the crowd that could purchase Burns’ freedom for a fair price. And, later, this was done.

Burns returned to Boston, later studied at Ohio’s Oberlin College and then became a Baptist minister. On July 27, 1862, just seven weeks before Lincoln would issue his Emancipation Proclamation, 28-year-old Anthony Burns died in Canada from tuberculosis. As much as anyone, Burns had exposed the gaping divisions between North and South that would lead to disunion and Civil War.

There are several audio versions included in the Black Abolitionist Archive, and the published speech by Anthony Burns is one of them. The recorded voice of a volunteer reader of this speech adds depth and another perspective on this important part of history.

In 1854, Emerson wrote: “Ask not, is it constitutional. Ask, is it right?”