“Where is Charles O’Conor?”

The U.S. Civil War officially began in the early months of 1861. Rumblings of war and early warning signs were very apparent in the months and years preceding this official date, however. Members of the free black population were already taking steps during this time to sabotage what they called the “slavocracy” as an economic institution. And they were doing a great job of it. Slowly but surely each patient step toward disruption through “agitation” (as they called it), legal wranglings, and speaking engagements was making an impact.

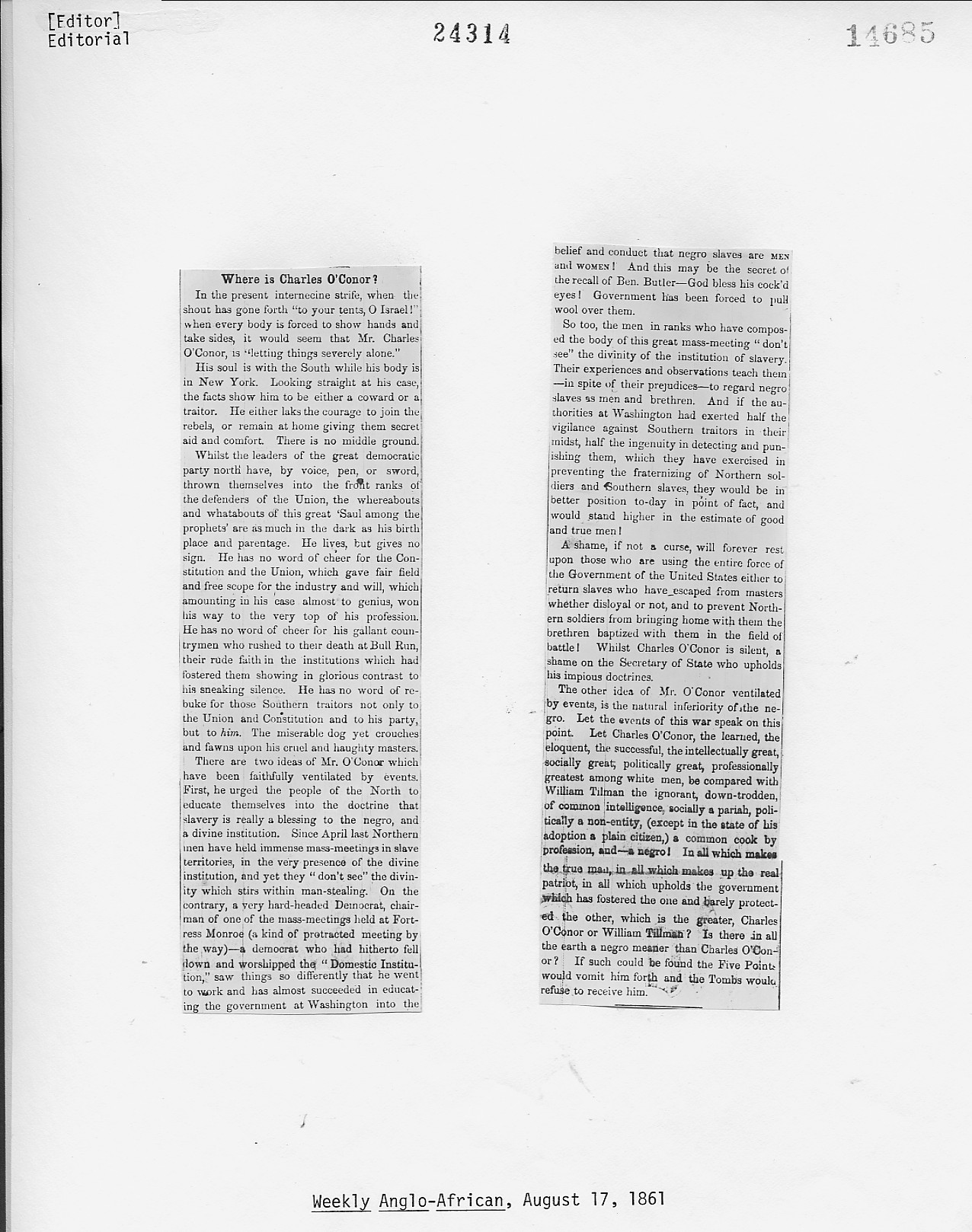

In August, 1861, an editorial appeared in the Weekly Anglo-African newspaper. The call was for Charles O’Conor, attorney, would-be politician, and pro-slavery advocate to step up now with his reasoned commitment to an institution that war was finally killing off. At this early part of the war, O’Conor was nowhere to be found, neither siding with the North (where he lived) or the South (where his allegiance lay). Stern, outspoken, and fixed in his ideas about what was best for the U.S. economy and the country in general, Charles O’Conor represented everything that was wrong with the political system at the time. His focus was on money, growth, and enterprise with very little consideration to the suffering of the humanity involved in bringing this about. The writer tells his readers that O’Conor’s opinion was that slavery was “a blessing” to the slaves, who he considered as little more than animals.

The writer of this editorial was speaking with some knowledge of recent history involving O’Conor that he shared with his readers. In this may be subtly referenced a particularly interesting court case that O’Conor was involved in some ten years prior in 1852.

Jonathan and Juliet Lemmon were traveling from Virginia to Texas with their eight slaves. As part of this trip, they traveled to New York to await a steamer heading south. While in New York, their slaves were housed at a boarding house and came to the attention of Black Abolitionists there. A website devoted to the case tells us what happened next:

“Early the next morning, a writ of habeas corpus was presented to Judge Elijah Paine of the New York Superior Court by Erastus D. Culver, a local attorney and abolitionist, saying that the black people now at 5 (sic) Carlisle Street were restrained of their liberty and ought to be freed based on the 1841 repeal of the ‘nine months law.’ That law had been a provision in an 1817 act that had provided for the gradual abolition of slavery in New York State, and had permitted slaveholders to retain their slaves in New York if their stay was less than nine months. The repeal had not been tested since it was passed eleven years earlier. The writ of habeas corpus itself contained many errors that suggested no one had actually talked to the African American family at this point, but had only seen them at a distance. In it, Jonathan ‘Lemming’ was described erroneously as a ‘negro trader.’ But Judge Paine acted promptly, and the writ was served on Lemon that morning, with the black family taken into custody.”

As it turned out, the State of New York won this case despite O’Conor’s participation on behave of Mr. and Mrs. Lemmon. The slaves were ordered to be set free, and Lemmon took his case to the Supreme Court of New York ready for a further fight for them. The war soon interfered, however, and the court battle ended there.

This wasn’t the only court case O’Conor was involved in regarding the issue of slavery, but it hopefully opened the eyes of a man who viewed the entire black population as “inferior.” This one case offers a great example of how an entire race of human beings were able to use whatever means was at their disposal to fight this unjust institution. In the end, it took war to finally close this down, but it was ready to crumble long before this by a continuous weakening of its foundation by those inside it.