The Pastry War

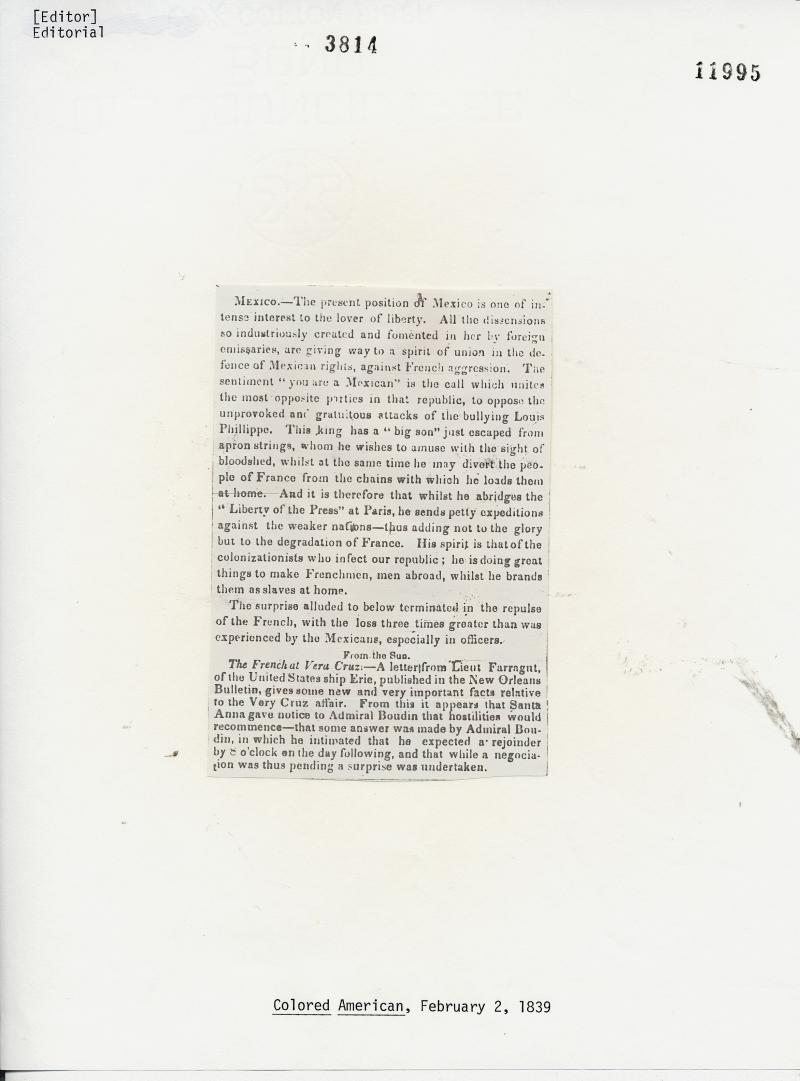

History has a way of smoothing the bumpy timeline that leads from “then” to now, and only bringing to the surface those events which made the biggest impact on the course of human development. Pity. A lot of interesting stuff gets covered over in the process of this. Take the Pastry War, for example. This was a minor footnote in the vast spreadsheet of historic events in the early years of this country’s development. Although it was seemingly inconsequential, news of this confectionery conflict ended up mentioned in an editorial in the February 2, 1839, issue of the Colored American newspaper, a weekly New York publication (1836-1842).

The importance to the Colored American then, was the idea of freedom, liberty, justice, and the rights of the individual. Here, they were saying, is an example of a poor country, dominated by a much larger one. Here is the power of the little guy fighting for his rights.

And Monsieur Remontel (the pastry chef in question) wasn’t the only one with an axe to grind. Mexico was particularly lawless during this period and several French citizens living there were caught in the mess of the governmental chaos. The response by France to go to war on behalf of its citizens living in Mexico was basically just an excuse. The French government had just had it with Mexico’s inability to pay its debts and its basic “drunken sailor” governing practices.

Was this a fight for the rights of the little guy, or a struggle between two ruling powers unwilling to work together to solve a relatively minor issue? The cause of one determined pastry chef for justice became lost in the belly-to-belly confrontation of two powerful men: the King of France and the President of Mexico.

According to Wikipedia, the Pastry War (also known as the First Franco-Mexican War) began innocently enough. In November, 1838, a French pastry chef named Remontel contacted the King of France, King Louis-Philippe, claiming his shop in Mexico City had been looted and destroyed by out of control Mexican officers. Mexico was in a state of flux during this time, and corruption and abuse of power held sway over the population.

The initial event soon devolved and Wikipedia tells us what happened next:

“France demanded 600,000 pesos in damages, an enormous sum for the time, when the typical daily wage in Mexico City was about one peso (8 Mexican reals). More importantly, the government of Mexico had defaulted on millions of dollars’ worth of loans from France. Diplomat Baron Antoine Louis Deffaudis gave Mexico an ultimatum to pay, or the French would demand satisfaction.

When president Anastasio Bustamante made no payment, the king of France ordered a fleet under Rear Admiral Charles Baudin to declare and carry out a blockade of all Mexican ports from Yucatán to the Rio Grande, to bombard the Mexican fortress of San Juan de Ulúa, and to seize the city of Veracruz, which was the most important port on the Gulf coast. French forces captured virtually the entire Mexican Navy at Veracruz by December 1838. Mexico declared war on France.”

The U.S. territories got involved, of course. The blockade encouraged smuggling through the Republic of Texas, and Santa Ana came out of retirement to join the fighting.

It was all over after a few months, ending in March, 1839, when the British got involved and brokered for peace. This wouldn’t be the last time these two countries would come to blows, however.

Reading the account in the Colored American offers insight into how this event was understood at the time. Although the writer of this editorial was not an eyewitness to the war first hand, he offers an interesting take on reports coming out of the thick of the fighting. This offers a perspective that links the reader to the times; and not just what was taking place in Mexico but in the general worldview of 19th century politics.