Love and Freedom

This month we celebrate two of the most valued aspects of human existence: love and freedom. Valentine’s Day (observed in remembrance of St. Valentine) focuses our collective attention on romantic love. We traditionally celebrate this holiday on February 14, by offering those dearest to us acts of love and devotion usually in the form of something sweet and beautiful: candy, flowers, poetry, sentimental cards, etc.

February is also Black History Month. This month is filled with events that recognize the contributions both powerful and inspirational of people of African descent. From its humble beginnings in 1915 (50 years after the passing of the Thirteenth Amendment officially ended slavery in this country), this formal recognition has evolved to include a strong focus on historic people and events; lectures, group celebrations, and an increased awareness of the evolution of the American identity.

The following story from the Black Abolitionist Archive is our contribution to this celebration of love and freedom.

William and Ellen Craft were both born into slavery in the early-1800s. When they were both in their early 20s, they were married. It wasn’t long after this marriage that they began to plan their escape to freedom from their living situation on a plantation in Macon, Georgia to the freedom available in Philadelphia, a trip of over 1,000 miles.

Ellen Craft, being of mixed race, was fair skinned and could pass as someone of Caucasian ancestry. They devised a plan that would use this fact to their benefit. While it seemed likely that Ellen could travel among the white population without too much attention, they determined that dressed as a man, she would have a better chance of eluding all suspicion and the limitations that a woman traveling alone might encounter. William, dressed as a slave valet to his traveling master, accompanied the disguised Ellen on their trip to Philadelphia.

At the time, slaves were sometimes allowed to earn extra money while working at jobs outside their owner’s land. William earned overtime pay from a local cabinet maker over a fourteen year period for work arranged by his owner. By December 1848, he had managed to save $220.00. This money would be used to finance their escape.

According to the New Georgia Encyclopedia website Ellen, dressed as a southern slaveholder in trousers, top hat, and short hair, and William, playing his role of slave valet, boarded a train bound from Macon to Savannah, Georgia. In Savannah, they boarded a steamship for Charleston, South Carolina, and from there boarded another steamship bound for Wilmington, North Carolina.

In Wilmington, they boarded a train and arrived just outside Fredricksburg, Virginia in time to catch another steamship bound for Washington, DC. A train from Washington, DC, took them first to Baltimore, Maryland and finally over the Mason-Dixon line into Pennsylvania. Though the trip was fraught with the constant chance of capture, once they arrived in Boston, they finally felt as if their freedom was secure.

The Crafts journey to freedom came very shortly before Congress ratified the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

This romantic story doesn’t end in Boston, however. The Crafts were soon pursued by bounty hunters who discovered them there. Black as well as white Bostonians assisted the couple by hiding them until the danger had passed. No longer feeling safe, however, the Crafts set sail for England where they continued their work for abolition.

“Romance” is defined in several ways. Dictionary.com includes “… narrative depicting heroic or marvelous deeds [… ] usually in a historical […] setting.” I think this story qualifies. The story of William and Ellen Craft can arguably be told as one of the great romances of the 19th century in the United States.

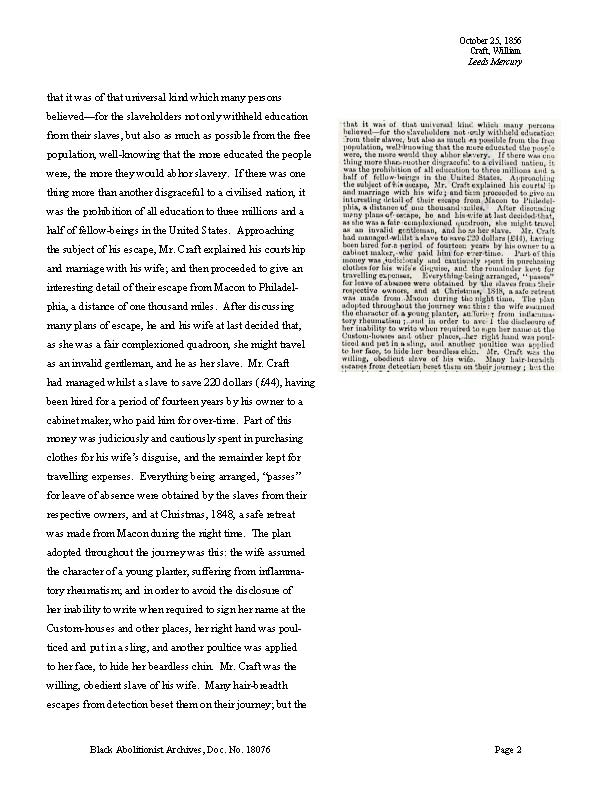

The excerpt below is page 2 of a 3 page speech delivered in England in 1856, soon after the Crafts arrived there. To read the entire speech, click here.

-

page 2 of 3, speech by William Craft reported in the Leeds Mercury newspaper in 1856

page 2 of 3, speech by William Craft reported in the Leeds Mercury newspaper in 1856