Time Travel Archive Style

Got a few minutes? How about a few hours? Somewhere in between perhaps? Maybe this weekend you’ve got some free time and are wondering how to spend it. May I suggest spending that time doing something worthwhile? With just a little bit of extra time you can offer yourself an amazing adventure, a wealth of knowledge, and a lot of interesting trivia. Step into the past with the click of a button and explore the university’s digital archives. You can choose from a number of eras to visit and learn a lot in the process.

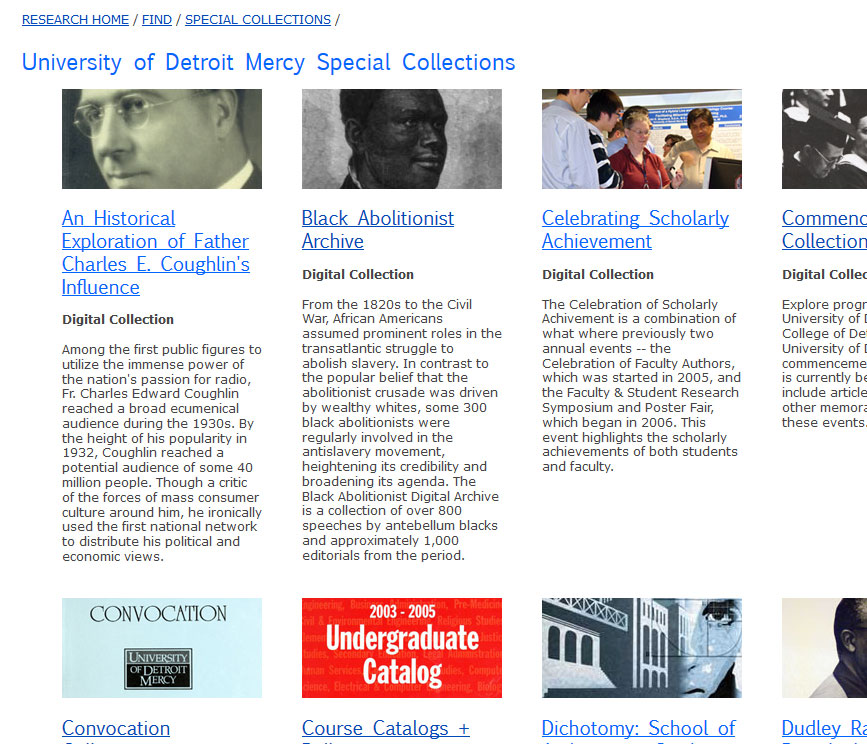

Interested in the 1930s? Click into the Father Charles Coughlin collection and learn about his unique perspective on the social world of his time. If you haven’t heard of his influence through radio broadcasts, I think you’ll find this a great place to start your journey. Expand this by visiting the Shrine Herald Collection.

What about the 1800s? This period was filled with triumph as well as heartbreak. The Black Abolitionist Archive offers you access to speeches and editorials that not too many people have read. These works allow you to see this period in our human history from another perspective than you may have previously had. The history of the university begins in the late 1800s, and perusing the writings from this period of time in the Tamarack collection and the University Histories collection is a great complement to these early archives.

Perhaps you’re interested in Mercy College. A great place to explore this great school is through the Mercy College Student Newspapers collection, the Commencement Collection, the Convocation Collection, and the Sisters of Mercy Collection.

We have a fine collection of original art from artist Maurice Greenia which is sure to please the art lovers among you. For fans of the unique, check out the Fr. Edward J. Dowling, S. J. Marine Historical Collection and the James T. Callow Folklore Archive. And who can resist the pages of the Tower Yearbook in our University of Detroit Yearbook Collection.

Remember football at the University of Detroit? It’s still there among the digitized programs in our University of Detroit Football Collection. Each program offers visitors a glimpse into a time when football reigned supreme at U of D.

And wait … there’s more! Stay for an hour or spend the day! There’s a lot of discovery waiting for you on our Special Collections page. Invest some quality time during these cold winter afternoons with history and learning. It’s a great way to time travel archive style!