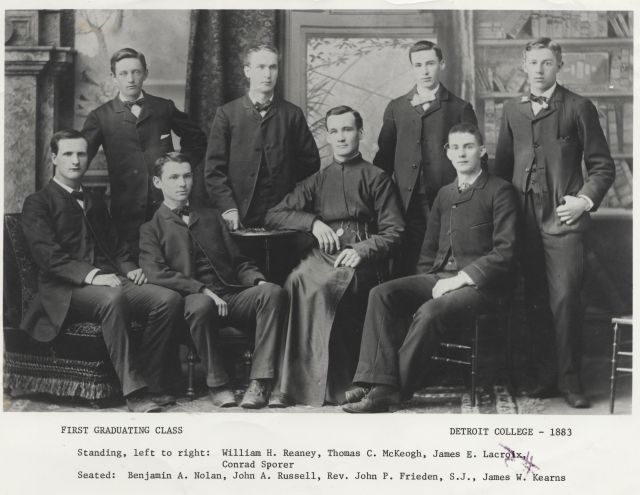

The Stadium

Ah, the good old days!

It wasn’t that long ago that fall meant football at the University of Detroit; and U of D football meant filling the Dinan Stadium. This stately “mission on the plains” stadium once stood in all its magnificence in a section of the campus that now offers a vast expanse of parking lot.

No story of the University of Detroit would be complete without mention of Dinan Stadium. In its heyday it graced the McNichols campus for just shy of 50 years. And if you ask most alumni who attended school prior to 1971, their memories of the campus then are likely to include the stadium and the grandeur of the events held there.

In 1923 when Dinan Stadium was completed, Harry F. Le Duc of the Detroit News, described how the “reposeful ruggedness and alabaster white against the sky” of the building itself impressed visitors. In his report, the story of this stately arena takes on a poetic presence befitting its place in the history of the university. So taken was Le Duc with the splendid architecture of this building that he gushed that “the dentils beneath the parapets provide the effect of light and shadow that is desired in accentuating the horizontal line.” What a sight that must have been! This one corner of the university was likely the grandest spot around. No wonder Le Duc was impressed. And no wonder this building held such sway over those who entered it for the first time. In its day, this stadium became much loved, and much identified with the university itself. The sheer expanse of it was enough to command respect and awe. (Read Le Duc’s eloquent report in the 1923 yearbook.)

After enduring years of cheering fans, countless throngs of gleeful students, and all the fanfare and drama that sports meant (and mean) to folks around here, this glorious stadium closed its gates for the last time in 1964. On November 30, of that year, everything came to a screeching halt when Varsity Football was discontinued at U of D. Students went nuts! 1,000 rioting students stopped traffic and took down traffic lights all along Livernois in their frenzied rage, all in the shadow of the darkened stadium. For a few years, it seemed to be waiting. Maybe there would be rescue, a resurgence of activity, a reclaiming of its part in the university experience. But while Club football had a temporary run, all football was finally ended for the University of Detroit by 1972.

So, it came to pass that in 1971, the stadium was demolished to make way for more parking, its end a mere footnote in the events of that turbulent year, commemorated only by a skeletal image of the last of it on the front of the 1972 yearbook.

It’s a sad testament to its glory to realize that while Dinan Stadium was welcomed to campus with such poetry and grace – while it was revered over the years for its magnificence and praised for its splendor when it first opened its gates in 1923 – that only one photograph and a brief note bid it farewell in the 1972 yearbook.

“They paved paradise to put up a parking lot” – Joni Mitchell, “Big Yellow Taxi”