A recent documentary on Public Television (PBS) called The African Americans: Many Rivers To Cross offers an excellent overview of slavery in the United States from its early beginnings in the 1500s to its final end in 1865. This view aligns closely with the history recorded in the Black Abolitionist Archive’s editorials and speeches. Slavery wasn’t anything new when this country was first established. What WAS new, however, was the notion of “who” slaves were and how this tied in with racial discrimination. This didn’t start suddenly. When slavery was first introduced in this country, slaves (and indentured servants) were of many races, including Native Americans. This change was gradual, but at one point in the history of the United States, “slave” was equated with African captives.

Slavery offered the free labor that helped this country grow. It was good for the economy, it made many people wealthy, and there seemed to be an endless supply of slave labor just waiting for transport and sale. The presence of so many enslaved people in the U. S. offered a reminder of our collective wealth and also of our collective guilt. This was difficult to reconcile for many people. Social divisions by class soon included a division based on color. This began so subtly that when someone finally started paying attention to what was happening, they also recognized the dramatic (and unpleasant) potential for social change that would be required to correct it.

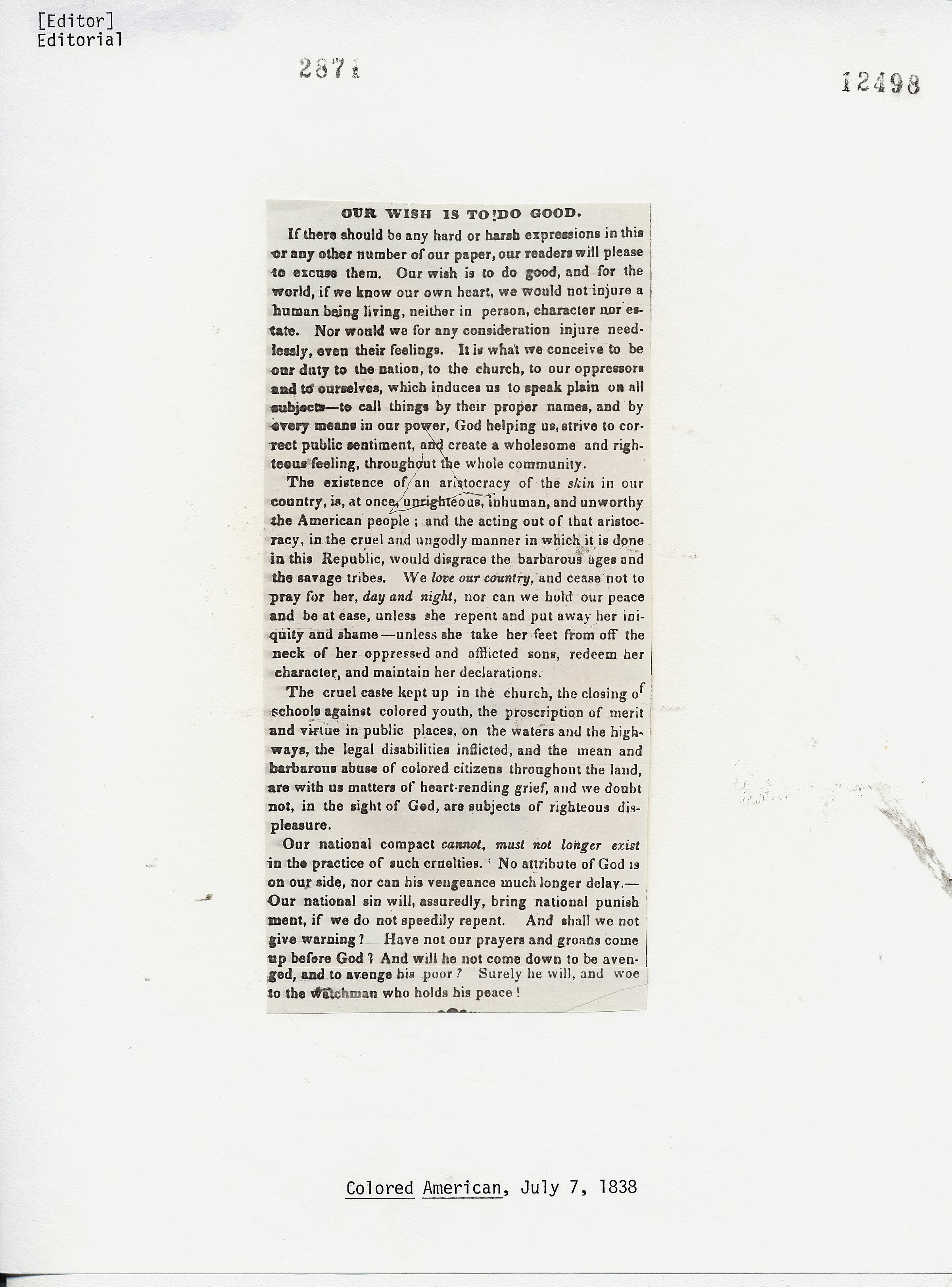

This country was not only built on the backs of slave labor, but also on a strong religious foundation. Treating fellow human beings as property, as little more than beasts of burden, seemed to counter Biblical teachings that spoke of brotherhood and love. The institution of slavery not only contradicted these teachings, it also contradicted the Constitution itself (the “self evident” statement that “all men are created equal” was difficult to ignore).

In order to bridge this gap in reason, some sort of justification was necessary, and towards the end of its well-held place in the American economy, a justification of slavery was the subject of many papers, books, and speeches. The rationale for continuing slavery ranged from creative logic to junk science to religious benefit. Those defending the institution of slavery were nothing if not creative in their reasoning.

In the March 1, 1856 edition of the Anti-Slavery Advocate, William Wells Brown discusses a book by Dr. Nehemiah Adams that had recently hit the bookshop shelves. This wasn’t the first publication to offer a justification of slavery based on Biblical teachings but it was one worthy of note.

William Wells Brown was an escaped slave who rose to prominence through his writings, lectures, and abolitionist work. It was during his attendance at the Cincinnati Anti-Slavery Convention in May, 1855, that he had occasion to offer commentary on Dr. Adams’ book that praised slavery for benefiting the “religious character” of the slave. The book described the author’s experience with “southern slavery” after a trip to the American south. It seemed the religious conservatives of this time, like Dr. Adams, were the main people wrestling with this problem of justifying slavery. William Wells Brown compared Dr. Adams’ writing to his own experience with a white minister’s family shortly after he (Brown) had escaped from slavery. During that visit, Brown had received such kindness from the minister’s wife and daughter (Harriet) that he was dizzy from it all.

The story may have ended there and the reader may have drawn the conclusion that Brown was rethinking his passionate resolve to speak against slavery from this minister’s pulpit. He liked the family and had no desire to upset them or make them regret their kind hospitality. He considered toning down his speech, and adjusting his remarks. The last paragraph, however, sums up his thoughts nicely:

“But I had a bond of sympathy with the slave that Dr. Adams had not. The little girl Harriet reminded me that I once had a sister; that she was torn from me and sent south; that I had not dared remonstrate, or even call her sister. The kindness of the lady whose hospitality I was then enjoying brought to mind my mother, from whose caresses I had been torn, and how she had been sent I knew not whither, never to see her boy’s face again. I therefore resolved to do my duty, and I did it.”

We’re proud to include with this digitized speech an audio version recorded by a volunteer. Click this link to view the entire record.