April marks the 30th anniversary of The Poetic Express, Maurice Greenia, Jr.’s publication offered free of charge to one and all. It was 30 years ago that Maurice began working at Crowley’s Department store and decided to offer his unique perspective to the people of Detroit. The first volume (available in 1985 and 1986) was the result.

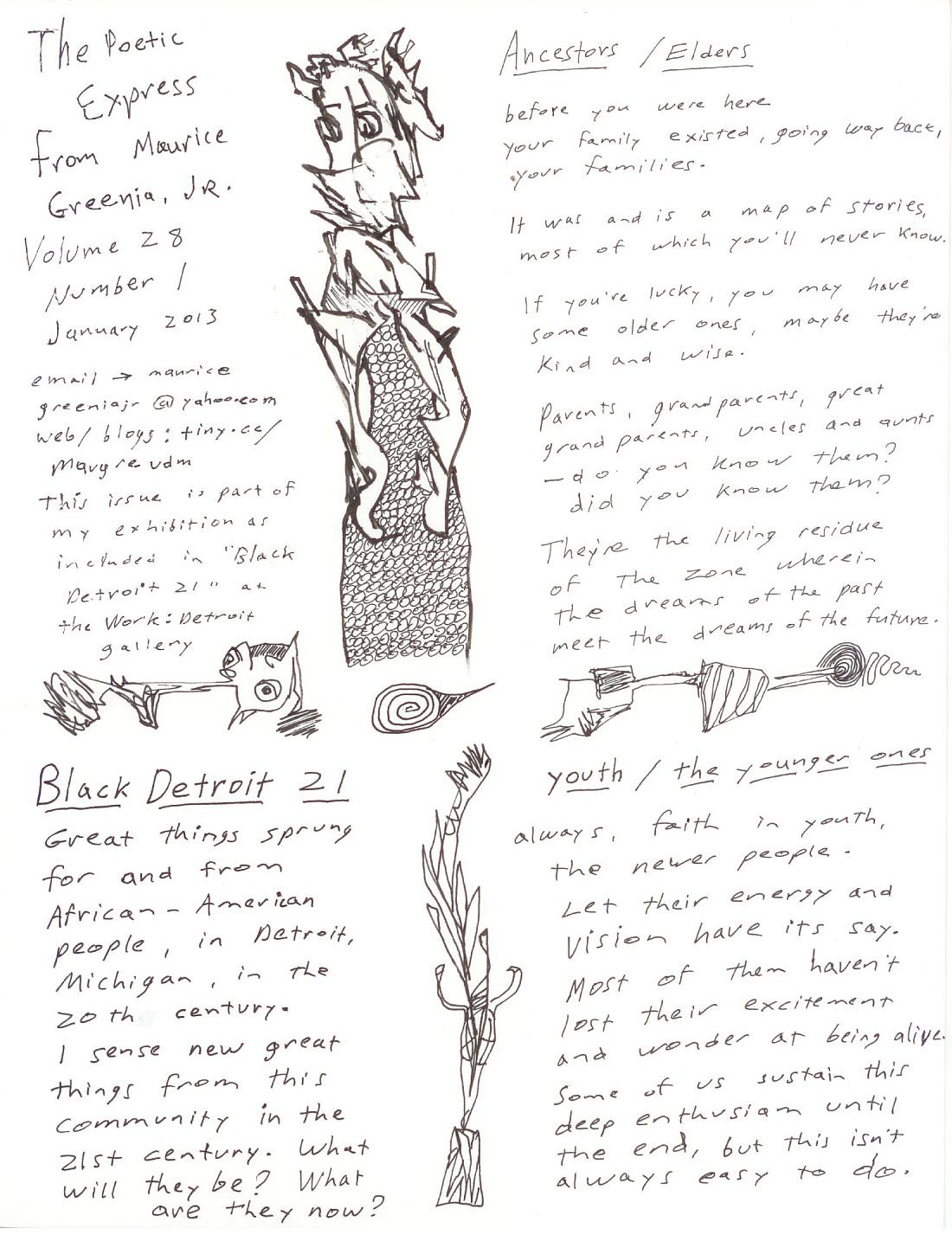

Each issue of The Poetic Express combines drawings, poetry, and Maurice’s (aka Maugre’s) unique take on an ever changing and sometimes confusing world. You can find these one of a kind creations in digital format in the Maurice Greenia, Jr.’s archive.

Maurice sums up the 30 year history of The Poetic Express this way:

“In 1976, I started to type up my writing and poetry, make copies and pass them around. By April 1985, I’d decided to put out a monthly publication called, The Poetic Express. Thirty years later, it’s still going strong. I’ve never missed a month. I usually put out two pages, one of which includes my comic strip “Surreal Theatre.” For a long time, I did a yearly “Emotional Digest” feature, with poems on emotions.

Usually in December, I do a “Dedications Issues,” with poems dedicated to some of my favorite people, both past and present. These are mainly my “art heroes.” I’ve mailed out hundreds of pages by postal mail. This has slowed down some, but I want to get back to it. If anyone gets a stamped self-addressed envelope to me, I’ll mail them a sample issue.

Over the years, I’ve passed The Poetic Express out to people I run into. This usually happens at events such as movies, concerts, art openings. People who know me come up and request an issue or two. People have told me that they appreciate, even treasure these. The Poetic Express seems to have encouraged some sort of “underground cult following.” A few people have even told me that my poetry in these issues helped them through some bad times.

I’ve done various events and exhibitions for the other major Poetic Express anniversaries: 10 years, 20 years and 25 years. My parents are fans, and my dad likes to read the new issues out loud to my mom. Occasionally fans have given me detailed responses to specific poems, either orally or in writing.

I like The Poetic Express because it lights a fire under me to write poetry every month.”

(Find more information on Maurice’s blog site.)

The first page of the most recent volume of The Poetic Express is shown here. But don’t stop at the first page! The entire issue is a magical journey through art in a poetic way. This is a trip you won’t want to miss!