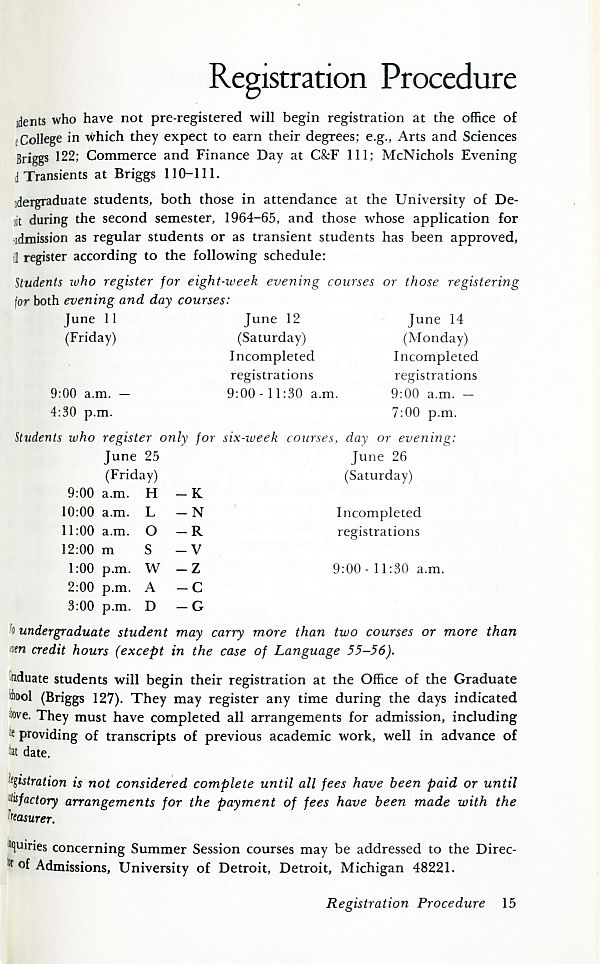

The 1965 Campus

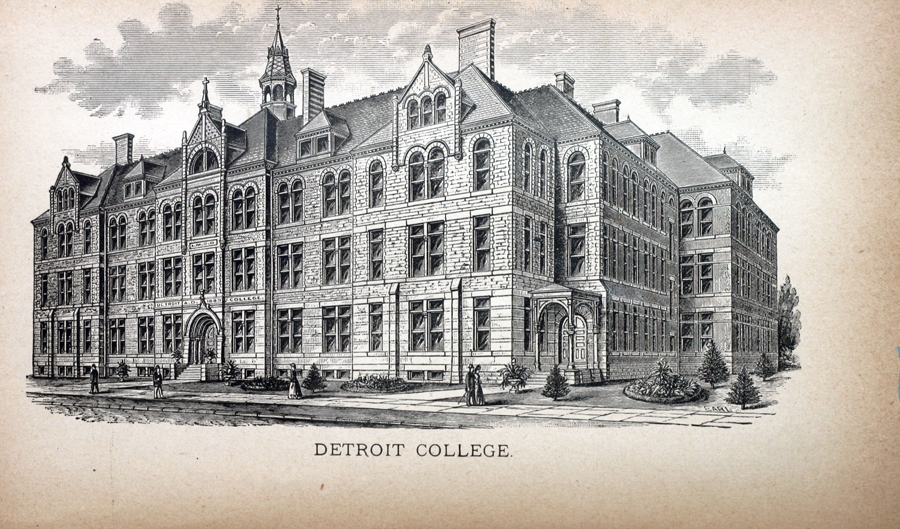

There are two great aerial photos of the campus in the beginning pages of the 1965 Tower Yearbook. All the changes that have taken place on campus and the surrounding neighborhood since this time are easy to see from this vantage point.

Some readers might recognize the Dinan stadium in the first image. What was once referred to as a stately “mission on the plains” when it was first built in 1923, came to a sad and deserted end just months before this photograph was taken. And while it had graced the McNichols campus for almost 50 years, it was unceremoniously bulldozed in 1971 to make way for more parking and the Titan Track and Field area we enjoy now.

And speaking of parking, it’s interesting to see the creative solutions to the growing parking problem students encountered when this first photograph was taken. Back then, cars could drive through campus on a couple of small connecting streets. Parking was at a premium and available spaces were scattered around the campus (as this photo shows). In those days, finding a place to park was basically a matter of luck. This was becoming a major problem and the razing of the stadium helped.

This photo also shows an empty section of the campus across from the Engineering building and clock tower that would one day hold the student center and ballroom. The older buildings pictured here offer indicators to help imagine the newer ones. It’s interesting too to realize how many of the surrounding homes would be completely gone in the fifty years that followed.

For one brief moment, the shutter on someone’s airborne camera, captured a slice of 1965 campus life. It’s unlikely that this lone photographer could have had any idea how important to campus history his (or her) photograph would become.

Want more? Visit the Tower Yearbook digital collection and discover the treasures of the past waiting for you there.