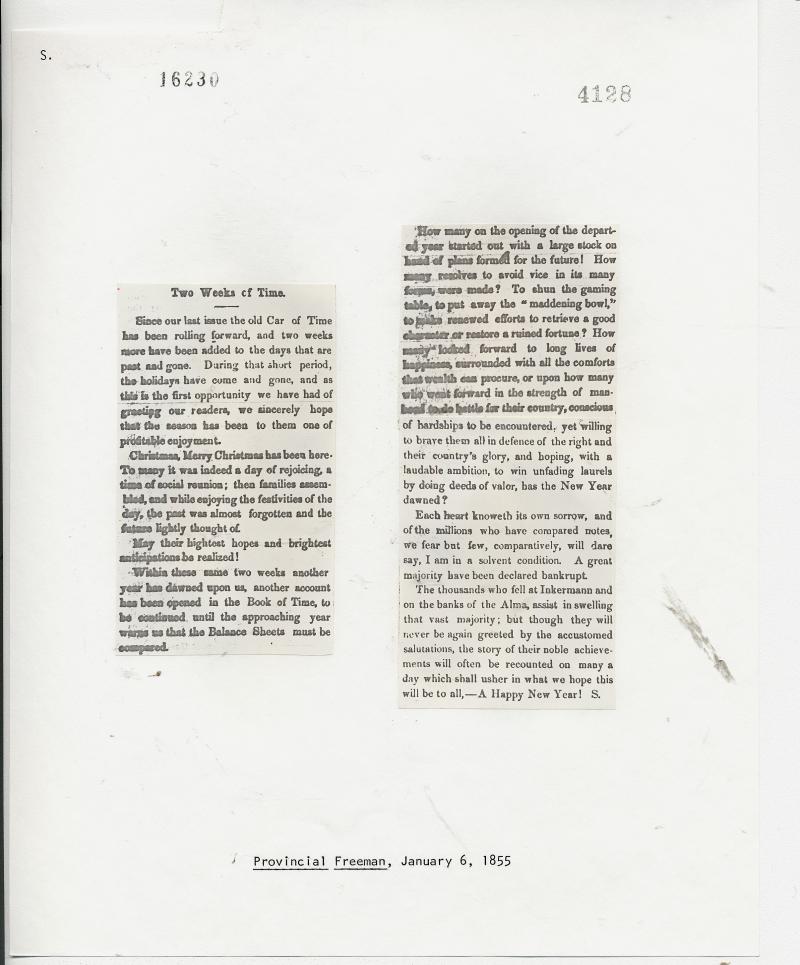

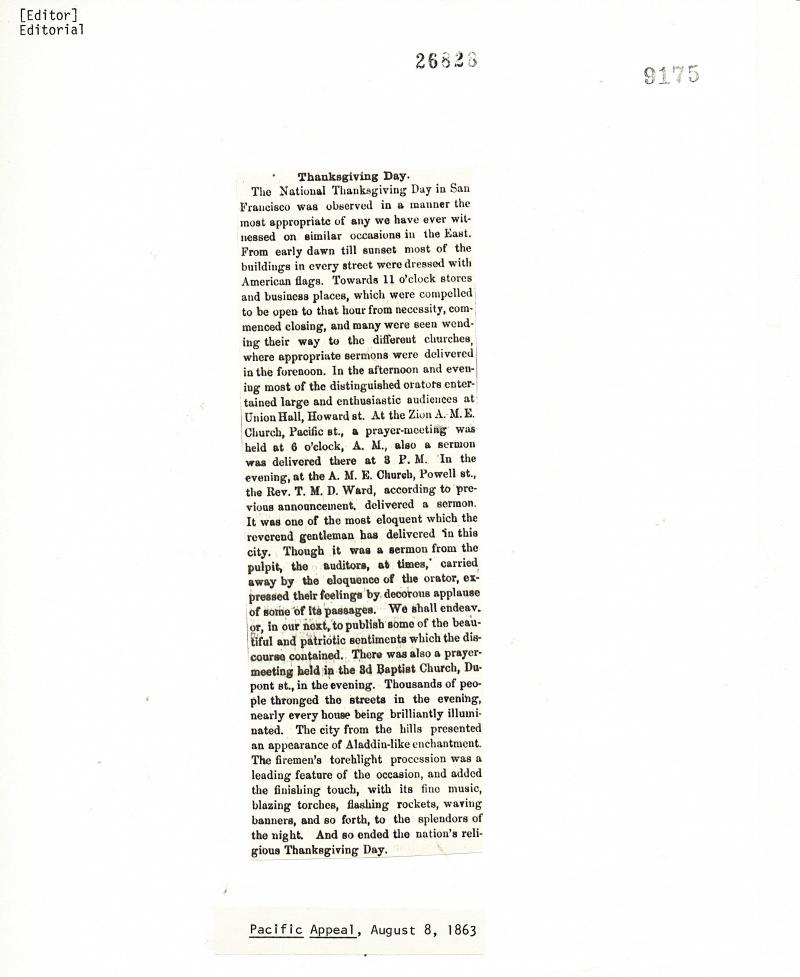

A Note on the New Year from 1855

The following editorial was published in the Provincial Freeman newspaper on January 6, 1855. The digitized version of this editorial in the Black Abolitionist Archive allows us to bridge the expanse of 161 years, and merge in time with the author who signs her name simply as “S.” (This is probably Mary Ann Shadd who edited the newspaper during this time.) Although so much historic change has taken place since this editorial was written, it seems today’s readers will recognize how relevant the sentiments are here.

I’m including a transcribed version of this editorial here for reading ease. But in order to gain a full experience of the connection in time, please visit the original article here:

“Two Weeks of Time

“Since our last issue the old Car of Time has been rolling forward, and two weeks more have been added to the days that are past and gone. During that short period, the holidays have come and gone, and as this is the first opportunity we have had of greeting our readers, we sincerely hope that the season has been to them one of predictable enjoyment.

Christmas, Merry Christmas has been here. To many it was indeed a day of rejoicing, a time of social reunion; then families assembled, and while enjoying the festivities of the day, the past was almost forgotten and the future lightly thought of.

May their brightest hopes and brightest anticipations be realized!

Within these same two weeks another year has dawned upon us, another account has been opened in the Book of Time, to be continued until the approaching year warns us that the Balance Sheets must be compared.

How many on the opening of the departed year started out with a large stock on hand of plans formed for the future! How many resolves to avoid vice in its many forms, were made? To shun the gaming table, to put away the “maddening bowl,” to make renewed efforts to retrieve a good character or restore a ruined fortune? How many looked forward to long lives of happiness, surrounded with all the comforts that wealth can procure, or upon how many who went forward in the strength of manhood to do battle for their country, conscious of hardships to be encountered, yet willing to brave them all in defence of the right and their country’s glory, and hoping, with a laudable ambition, to win unfading laurels by doing deeds of valor, has the New Year dawned?

Each heart knoweth its own sorrow and of the millions who have compared notes, we fear but few, comparatively, will dare say, I am in a solvent condition. A great majority have been declared bankrupt.

The thousands who fell at Inkermann and on the banks of the Alma, assist in swelling that vast majority; but though they will never be again greeted by the accustomed salutations, the story of their noble achievements will often be recounted on many a day which shall usher in what we hope this will be to all, — A Happy New Year! S. “