Headache Cure

The James T. Callow Folklore Archive is an interesting place to spend some time before the summer ends. A visitor can usually discover something interesting, funny, or amazing there. Each entry is brief but loaded with a bit of America that few other collections offer.

Take this post, for example. I was searching for something to write about and typed a few lines into Google to see what I could find. To my delight, this brief story from the collection popped onto the page:

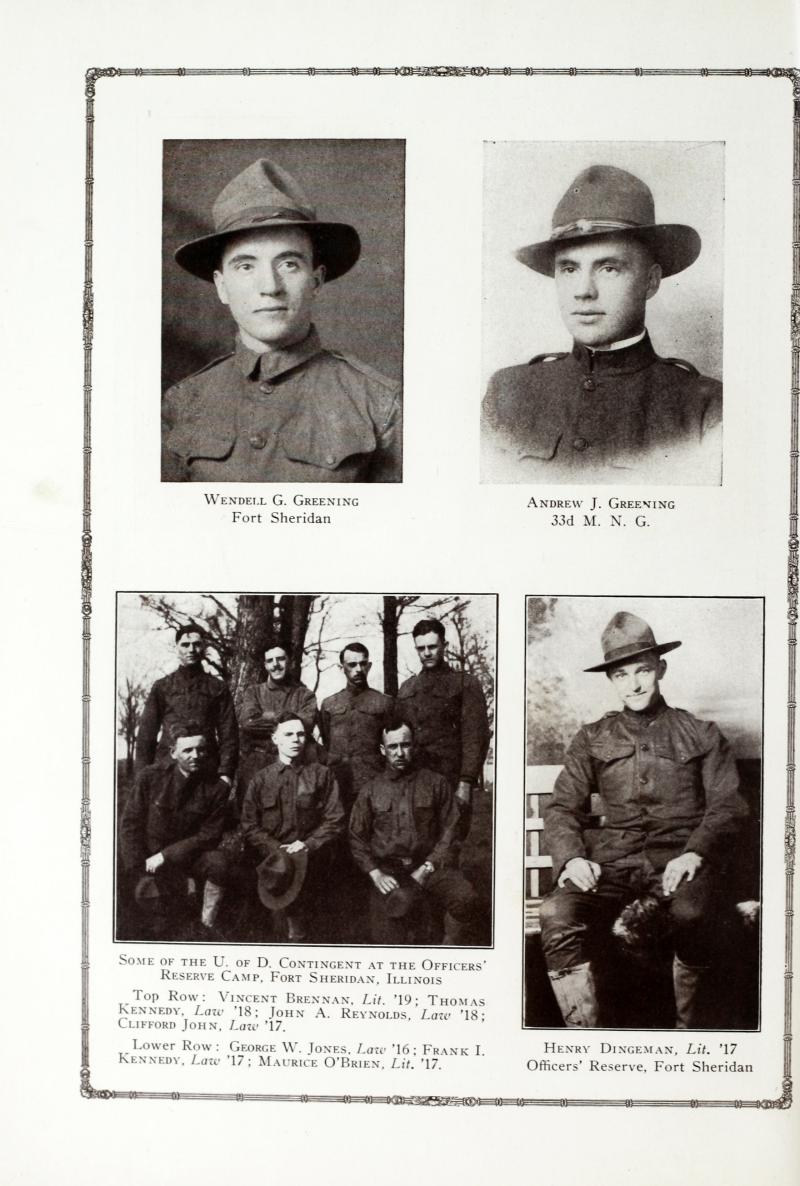

TILLIE VOSS WAS THE HUGE FOOTBALL PLAYER FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF

DETROIT IN THE YEAR OF ABOUT 1926. ONE DAY HE HAD A TERRIBLE

TOOTHACHE (SO THE STORY WAS TOLD FROM MY FATHER HOWARD

PHILIPPART, THE FULLBACK FOR U OF D). ASPIRIN DID NOT SEEM TO

HELP AND HE DESPERATELY NEEDED SLEEP FOR THE BIG NAVY GAME

THE FOLLOWING DAY. “I GOTTA DO SOMETHING,” HE TOLD MY FATHER

AND RAN FULL TILT HEAD FIRST INTO THE CINDER BLOCK WALL. AS

THEY CARTED HIM OFF TO BED FOR A GOOD NIGHT SLEEP, THE PLAYERS

SILENTLY APPLAUDED HIS DEDICATION AND LOYALTY.

This, to me, is why the term “holy moly” was invented. The U of D football players of the 1920s were indeed solidly built and … um, “head strong”!

The introduction to The James T. Callow Folklore Collection tells the reader more about this unique archive:

“The University of Detroit Mercy Digital Folklore Archive, founded in 1964 by Professors Frank M. Paulsen and James T. Callow was donated to the University of Detroit Mercy Libraries /Instructional Design Studio in 2009. The archives is comprised at this point of over 42,000 folklore traditions taken from field notes gathered by UDM (formerly University of Detroit) students as part of their course work in ‘Introduction to Folklore,’ ‘Studies in Folklore,’ ‘Folk Groups,’ and ‘Folklore Archiving.’ The folklore archive covers traditions gathered between 1964 and 1993. Included in the Archive is the Peabody field note collection containing approximately 12,000 entries from Tennessee and the Southeast.”

Sounds interesting, right? To discover more, visit this wonderful archive by clicking here.