Changing Seasons

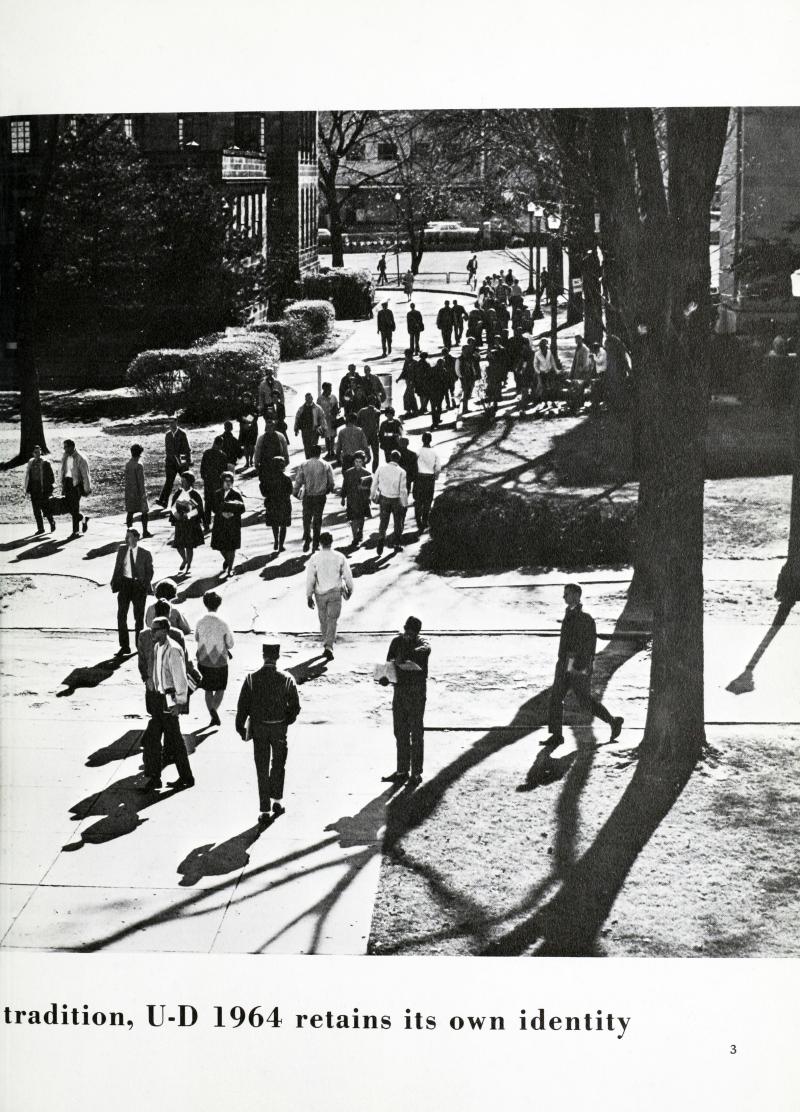

The very first Tamarack (volume 1, number 1) was published in April 1897. That spring must surely have begun in a similar fashion to the way it begins today: hopeful, bursting with flowers, sunshine, and the unspoken promise of a fresh start. The students who haunted the hallowed halls of Detroit College back then must have welcomed the end of winter with as much enthusiasm as today’s students. Spring meant a release from negotiating the icy streets, the snowy treks to campus, the unyielding freezing temperatures, and the general mess of winter. Back then without the advantages of current cold temperature attire, it must have taken a lot of determination just to get to class. And how wonderful it must have been to at last know the sun would grace those final days of classes before the end of the semester.

The change in seasons reflected the upcoming change in the century. The potential for amazing advancement ushered in with the arrival of the 1900s likely weighed on the minds of students in similar fashion to the potential for new life that the warmer season usually seems to promise. These two major changes surely helped influence the birth of this new publication. Reading through the first few issues it’s easy to be transported to a time when winter was just a little more difficult to deal with, and spring was just a little more welcome.

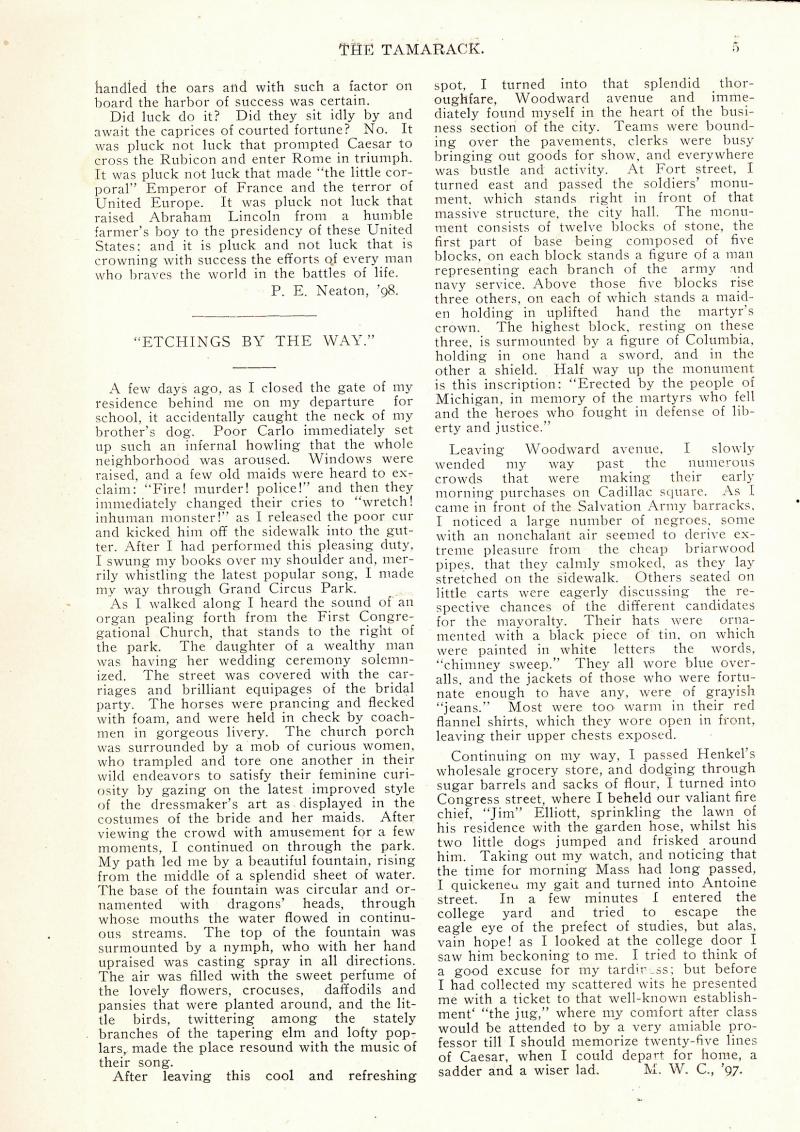

One of my favorite essays in the early Tamarack issues is the one published in this particular issue (shown below titled “Etchings on the Way”). This sort of descriptive work offers a rare glimpse into the world of the early student as he made his way along the streets of Detroit to class. (Keep in mind, this college was a man’s world back then.) The reader can join the writer as he makes his way along those early streets to his college classroom. His world was slower and quieter and he shares the sights and sounds of an average morning walk through the city.

Spend some time in this wonderful collection. You’re bound to find something interesting there.