Agitation

Agitation is an interesting word and one used often in the Black Abolitionist speeches and editorials. One definition offered by dictionary.com is: “persistent urging of a political or social cause or theory before the public.” This defining seems to fit, yet it also offers the idea that this type of action is at once determined and steady without being violent and aggressive. “Agitation” says “we’re not going away” as it demands change. While protest marches and rioting can spark immediate attention and forceful response in kind, agitation works slowly to alter the direction of a nation over time.

Agitation was a key determining factor in changing the mass mindset of a national belief in the economic gain of slave labor. While those in power were beginning to see the moral duty of ending this cruel institution, fears of retaliation and violence kept this sad slave-based system in place. A violent revolt would have worked against those who would be free. This had already taken place in Haiti during the slave rebellion there in 1791. The majority of slave owners in this country feared a repeat of this violence, with visions of being murdered in their sleep.

A steady demand for reasoned change is not something that would occur to a “naturally violent” segment of humanity. Those Black Abolitionists who realized that agitation was the best course for a long term solution were the heroes of this period. And so a steady stream of speeches, lectures, guest appearances, and public “slave narratives” allowed the message to reach those who placed God and reason over economic gain in this country and others.

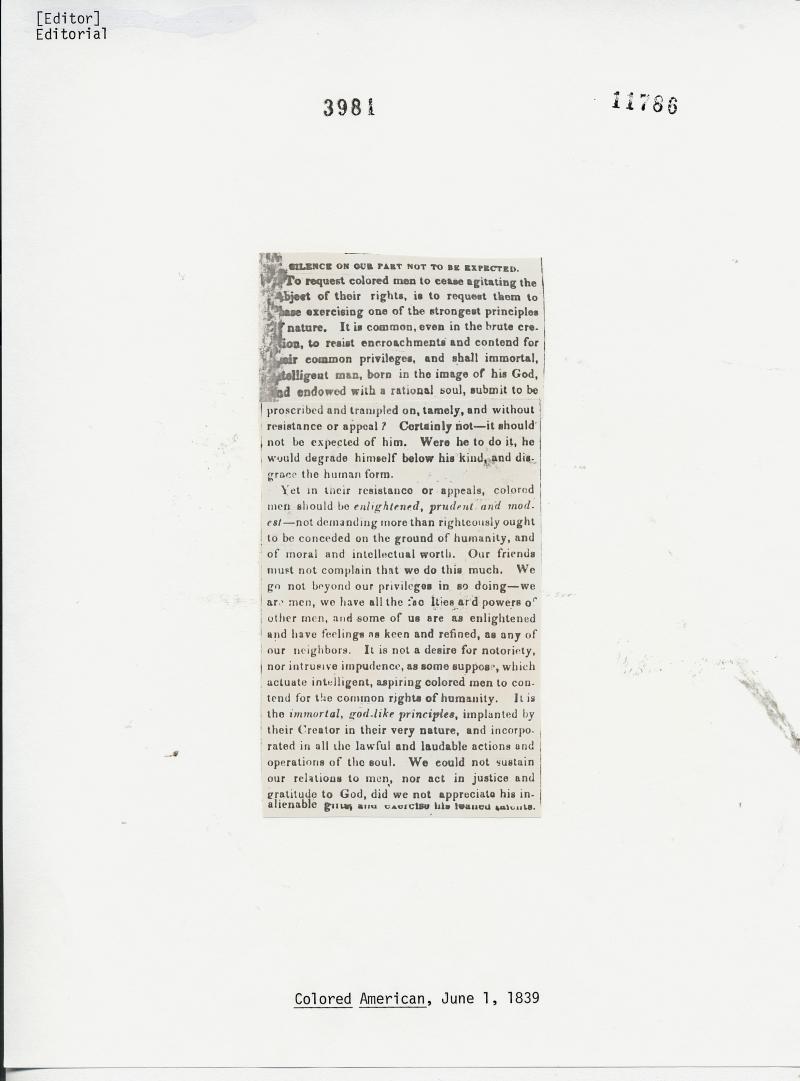

One writer summed up nicely the overall intention of those working toward the goal of freedom for the slaves. On June 1, 1839, a relatively short column appeared in The Colored American newspaper titled “Silence on Our Part Not to be Expected.” Even the title seems to say it all. In this article (shown here), the writer tells his readers that protest and appeals for justice should be expected from those working for the cause of freedom. He encourages their continued efforts, yet to approach this effort as “enlightened, prudent, and modest” people.